Definition:

Refers to the forward bend or curvature of the spine, and is a normal feature of the thoracic region of the back. The normal thoracic spine has a curvature of up to 40° on a lateral radiograph, measured from the 4th to the 12th thoracic vertebra.

Exaggeration of this curvature can become evident in certain circumstances, and in some cases this increased curvature of the thoracic spine may require treatment.

Causes of increased kyphosis include:

- Poor posture

- Scheuermann’s Disease (spinal osteochondrosis or idiopathic thoracic kyphosis)

- Congenital abnormalities (rare)

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Following trauma

- Increasing age & osteoporosis

Postural Kyphosis:

This is a flexible deformity which is not associated with any underlying bony abnormality. Poor posture and tight muscles in the legs and chest may contribute to the problem.

In this case advice, exercise and being made aware of a more correct posture when standing or sitting is usually all that is required.

Exercise may also help to relieve pain felt in the back associated with a poor posture, fitness and tone in the muscles around the spine.

Scheuermann’s Disease

Definition:

This is not a disease like measles or mumps, but a condition that is usually diagnosed following a lateral x ray of the thoracic spine. It should be more properly referred to as spinal osteochondrosis. It is also often referred at idiopathic thoracic kyphosis.

The condition is associated abnormal development of the vertebrae that results in the vertebrae becoming wedge shaped (shorter or lower at the front than at the back).

Clinical Features:

These changes are associated with an increased thoracic kyphosis and usually becomes evident in adolescents. Individuals with this condition may report discomfort in the thoracic region of the spine or in the lower back. Symptoms are more common during the period of rapid growth and will usually settle or at least improve significantly once the skeleton completes it maturation between 20 and 25 years of age.

Treatment:

In mild cases all that is required is observation and advice regarding correct posture and exercise.

In more severe cases, where there is still an expectation of considerable skeletal growth a brace may be recommended, and in this condition there is a good chance that the brace will halt progression, and in fact result in an improved posture once skeletal maturity is achieved.

If a brace is to be used it must be worn for 23 hours per day until growth has almost finished, and will then usually continue to be used only at night for a further six months.

In cases where growth has already neared completion or where deformity is severe surgical intervention may be considered or recommended. The exact degree of kyphosis that required correction is not clear-cut but in general the curve should be greater than 60°, progressive (getting worse) or where there is already a significant clinical deformity. Surgery may also be considered where there is persistent and significant pain and should be undertaken if there is evidence of spinal cord compromise or respiratory problems caused by the deformity.

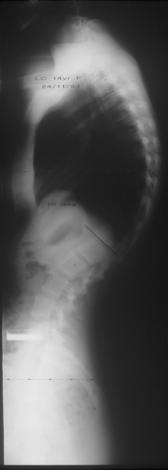

Below are the radiographs of a 14 year old boy with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who had what he considered to be an unacceptable clinical appearance and thoracic back pain. He underwent surgery to correct his posture and address his pain. This is however quiet major surgery and is not indicated in the majority of cases.