Scoliosis refers to lateral curvature of the spine. Deformity of this type may be “structural” and fixed, or postural and mobile.

Postural deformity is usually secondary to pain and muscle spasm or a leg length discrepancy. A structural deformity is characterised by the presence of vertebral rotation as well as lateral curvature. This causes a rib prominence on one side of the back and may also be associated with asymmetry of the shoulders and waist.

A postural deformity is corrected by addressing the underlying cause of the problem.

Structural Scoliosis Classification:

- Idiopathic

(i.e. no identifiable cause) - Congenital

Due to failure or formation and/or segmentation of vertebral elements during intrauterine development - Neuromuscular

Deformity results from the loss of muscular support of the spine - Other

Neurofibramatosis

Marfan’s syndrome

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Idiopathic Scoliosis:

This is the most common type of scoliosis and although the cause is unknown we do know that it tends to run in families, and that girls are more likely to be affected than boys.

Minor deformity, that may not even be recognised when someone looks at your back, is quite common and affects approximately 4% of the population. The male and female incidence is fairly equal for this type of curve.

More severe deformity, where medical review and regular checks are indicated is more common in girls. The male : female incidence of individuals requiring treatment being 1:8.

Clinically:

In most cases it is the presence of a deformity that leads to presentation.

It is important that your local doctor or specialist look for associated disorders or conditions (eg neurofibromatosis) that may be responsible for the deformity, and which may require treatment in its own right.

The presence of a “rib hump” is characteristic. This is best seen in the forward bend test. There may also be asymmetry of loin skin creases, breast and shoulder height and pelvic obliquity.

Back pain is no more frequent in patients with idiopathic scoliosis than in the general population.

Treatment:

The aim of treatment is to prevent severe deformity.

In most cases, all that is required in the first instance is observation over a period of time to assess if the deformity is progressive (i.e. increasing in magnitude).

Curves that are severe at the time of presentation may, however, require treatment without a period of observation.

The need to treat curves that are greater than 30° depends on several factors. The age of the patient, the extent or stage of skeletal maturation, the location of the curve and the clinical appearance of the patient.

In some cases brace treatment is considered appropriate, particularly in young children to delay surgical intervention until such time as the spine is large enough to use standard operative techniques.

In general terms brace treatment will not result in significant correction of the deformity evident at the time of presentation. Brace treatment will however often hold a deformity and prevent further progression. The brace does however, need to be worn for around 23 hours per day to be effective, and is usually required for a period of eighteen months to three years or until growth has almost finished. From this point the brace is then worn only at night for another 6 months.

As a result of the physical and social effect of confining a young girl in a brace for this period of time, the use of this type of orthosis has decreased significantly in the last ten years.

Treatment options should however be discussed with your specialist.

Surgical intervention and correction is indicated in the treatment of progressive curves greater than 40°, and for large curves (90° – 100°) without evidence of progression. Surgery is also indicated where the clinical appearance of the spine, the deformity, is already significant or unacceptable, as this situation is not likely to alter significantly after the completion of brace treatment.

Prognosis:

The probability of curve progression is related to the pattern of the curve, the magnitude of the curve, skeletal maturity and the age at presentation. No correlation has been found between progression and the sex of the patient, the extent of deformity, the presence of a family history of deformity or radiographic measurements.

Once established, the curve is likely to increase during the growing period.

The chance of undergoing further deterioration after reaching skeletal maturity is slight, but curves > 50° may increase at a rate of about 1o per year. Deterioration in this circumstance is however usually delayed for some years, with the deformity increasing as degenerative changes progress.

Larger curves in a younger child, and higher curves (upper thoracic curves) have a worse prognosis.

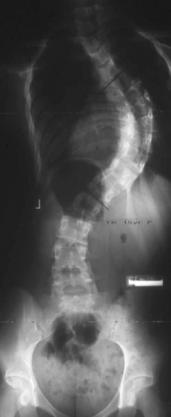

The images below are of the same 15 year old girl taken immediately before undergoing corrective surgery, and prior to discharge from hospital.

This girl gained 6.5 cm height, and was very pleased with the improvement in her overall appearance.